Sources

The sources consulted include documents and other records that can provide insight into the past. In addition to the written sources used in their INVESTIGATIONS, researchers also study audio recordings and pictures, visit the buildings where detainees were held, and conduct interviews with contemporary eyewitnesses.

Sources on the history of administrative detention

The majority of the written documentation has been preserved by public institutions: cantonal or communal archives, a number of special archives, the Swiss Federal Archives and libraries. Private archives maintained by institutions, associations or private individuals were also consulted where possible. In addition, the IEC conducted personal interviews with individuals who were subject to such measures or who were employed by the public authorities or institutions involved. Those interviews are also treated as sources.

The sources available do not present a neutral, unfiltered picture of a past reality. As a rule they represent only one perspective on the events. Moreover, not all documents or other records have survived, even where the events in question were relatively recent. The work of the Commission’s research team is now to identify from among the available material those sources that are of relevance to their research. In doing this they maintain a constant dialog between the selected evidence from the past and the continuously evolving state of present knowledge.

We present here a regularly updated sampling of sources used by the IEC researchers in their work.

|

|

|

||

| 1964/2017 | 2016 | 1929-1931 | ||

| Involuntary «voluntary guardianship» | Administrative detention as punishment for victims of sexual violence? | Everyday life in a labour facility described in a comic – the «Witzwiler Illustrierte» | ||

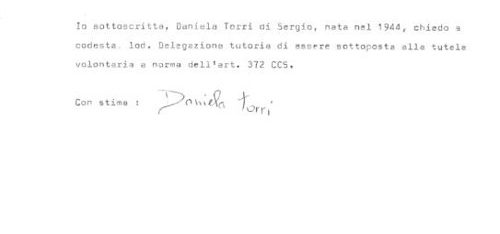

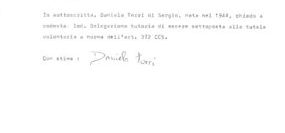

| Held in juvenile detention from 1960 to 1964, Daniella Schmidt was released upon attaining the age of majority, at which time the guardianship measure to which she had been subject as a minor came to an automatic end. At an interview with the IEC in 2017, Daniella Schmidt stated that, still very young at the time, she had been deceived by the guardianship authorities into signing a «voluntary guardianship» request, on 31 October 1964, and that she had been unaware of the real consequences her signature would have. | In her interview with the IEC, Mrs. T recounts how she lodged a complaint with the magistrate in charge of juvenile affairs against her landlord’s sexual advances and her financial exploitation at her work placement. As a result, she was condemned to administrative detention. | The artist of the «Witzwiler Illustrierte» (Witzwil magazin) recounts in colourful pictures episodes of everyday life in the labour facility and prison of Witzwil, occasionally pointing his finger against the administrative detention practice of the time. Between 1928 and 1931 the author was repeatedly imprisoned in Witzwil, where he engaged in artistic activities – no doubt to pass the time and entertain his fellow detainees. | ||

| Learn more | Learn more | Learn more |

|

|

|

||

| 1938 | 1921 | 1919 | ||

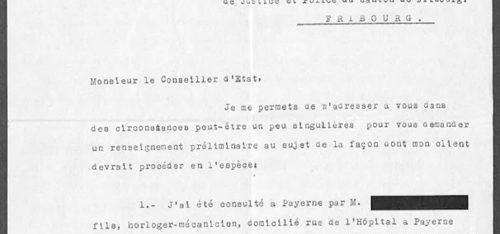

| A lawyer starts asking questions | Ways out of the correctional labour facility: a petition for release | A law on the administrative detention of alcoholics | ||

| On 24 June 1938, a lawyer wrote to the Department of Justice and Police of the Canton of Fribourg, requesting information about a female detainee being held at the Bellechasse facilities. A client of his, he stated, wished to marry her. The letter is written in a literary style, pleading in favour of the marriage. The lawyer expresses his astonishment at the fact that a woman can be held in detention in such an institution without having committed any criminal offence. | In the summer of 1921 A.B., an inmate of the Bellechasse correctional labour facilities, appealed to the Fribourg government to be released on probation, after he had already served half of his detention period. He alleged that he had always striven for an «irreproachable» conduct during his detention. | The first law in the Canton of Fribourg to permit the administrative detention of supposed alcoholics (both male and female) in correctional labour or alcoholic rehabilitation facilities was the «Act of 20 May 1919 on inns, the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages and the prevention of alcoholism» [Loi du 20 mai 1919 sur les auberges, la fabrication et la vente de boissons alcooliques et la répression de l’alcoolisme]. | ||

| Learn more | Learn more | Learn more |

ANALYSIS OF SOURCES

Selecting the relevant sources is the first step in the actual process of historical analysis. Different perspectives, different approaches and a never-ending succession of questions: The ability to deal with historical sources is one of the fundamental skills needed by researchers. It is their job to put the sources in context, to analyse them, and on that basis to formulate working hypotheses. In this way it becomes possible to get a better understanding of the interrelationships between events.

In the following, the most important steps in the process of source analysis will be briefly explained:

Description of sources

Before any source can be properly described, certain formal information must first be gathered. This makes it possible to categorize the sources preserved in the archives and to catalogue them in accordance with specific criteria (see examples below). The work of the Commission’s researchers rests on this preliminary processing of the sources, which is done in most cases by the archivists themselves. Researchers have a responsibility to mention this fact in their publications and to provide a systematic presentation of the references. This is to ensure that each source mentioned in the analysis can be easily located and consulted.

- SIGNATURE: The signature is an identification code: it indicates the name of the archive and of the specific collection in which the source is preserved. Each signature is unique so that there can be no confusion between the sources.

- TITLE: The designation assigned to the source, which also includes information about the content and the purpose for which it was established.

- DATE OF ORIGIN: This provides an indication of the time period to which the origin of the source can be traced.

- ORIGIN/PROVENANCE: Individual documents are normally found within larger sets of records, which are organised into collections. Here, information about the circumstances under which the sources originated plays an important role. The relevant information includes, among other things, the name of the organisation or person who created, processed or collected the records in question.

- FORM AND CONTENT: In addition to the title, this rubric provides further information on the content, the structure and the form of the source (printed or digital record, etc.).

- RULES OF ACCESS AND USE: Depending on the date of origin and the content, some sources may be classified and protected by a non-disclosure term.

- PHYSICAL CONDITION: Because of the condition in which they have survived, certain sources may not be available for consultation in the original.

GATHERING PERSPECTIVES

Once a sufficient number of sources has been collected, it is possible to begin the process of analysing them. Different perspectives on the sources are correlated with one another and existing studies on the subject are consulted. The end result is a scientifically based research report.

Publication of results

Books, newspaper articles, films, websites and other media are used to make the research results known to a broader public. In this way is possible for a widely shared understanding of the past to take shape. That understanding remains in constant flux and continues to evolve as new research becomes available. By making their results available to the public, researchers are thus able to contribute to the development of a nuanced and open-minded understanding of the past by the society in general.